On September 9th, 2020, the documentary The Social Dilemma was released onto the viewing-platform Netflix and by the end of October it had been seen by 38 million households. Written and directed by Jeff Orlowski, the docudrama includes first-hand accounts from tech-industry professionals, such as ex-employees from Google, Facebook and Apple, and presents their ethical concerns over social media business models. Despite the film’s somewhat awkward and heavy-handed dramatizations which I found made viewing slightly difficult at times, it is accessible to all, which makes it valuable content in this very necessary discussion. Although the consequences of globalised smartphone usage have already been the subject of debate and controversy, the documentary successfully brings the problem closer to home by exposing some shocking facts and figures on children’s mental health as well as modern political unrest. Whilst this Netflix documentary is a good resource, especially for teens to understand the consequences of our media age, the conversation cannot stop there. This article aims to further investigate some of the issues raised in The Social Dilemma by exploring research papers and events that affirm or challenge some of the documentary’s claims on what leads to tech addiction and the dangers of it in regards to fake news and mental health.

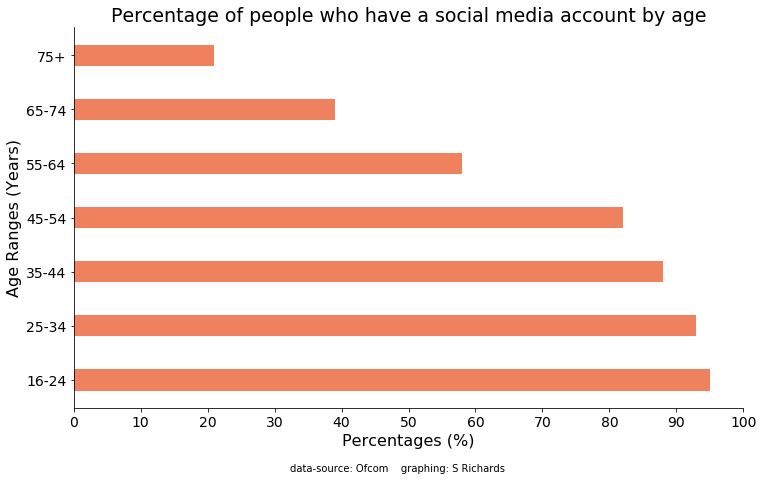

Ofcom’s annual “Adults’ Media Use and Attitudes Report” (2020)1 found that in 2019, 81% of UK adults were using a smartphone and spent an average of over 3.5 hours online every day. During the first covid-19 lockdown in 2020, this figure rose to over 6 hours. This engagement provides the opportunity for an entirely new way of marketing which has created the richest companies in the world. The reason why signing up for a social media account such as Facebook, TikTok or Instagram requires no financial cost for the user lies in the fact that their mere presence on the app is a money-making resource. These tech giants are powered by engagement growth and advertising, two targets achieved by the most revolutionary change in the data-processing landscape to date: machine-learning. As a subset of artificial intelligence and a rapidly developing field of science, machine-learning is the closest humanity has come to making technology that thinks for itself. Once an algorithm is created, it develops autonomous characteristics that learn and adapt through experience and data, without the intermediary of human effort.

“Just as electricity transformed almost everything 100 years ago, today I actually have a hard time thinking of an industry that I don’t think AI will transform in the next several years.”

Andrew Ng, Why AI Is the New Electricity

The Social Dilemma concisely describes how machine-learning is used by social media companies to make profit. By examining your online habits, the algorithms develop and improve, in such a way that they can predict with increasing accuracy what posts will attract your attention. This tailored inventory of content becomes your ‘feed’ and the longer you spend there, the better the app becomes in holding you hostage. This persuasive technology is incredibly sophisticated, taking into account details such as the number of seconds you pause on a post and other unconscious scrolling habits. This has allowed for the most profitable development in advertising in the history of mankind. We are exposed to attuned advertisements at the precise moment we are predicted to be the most vulnerable to them. To demonstrate how successful this marketing scheme is, we can take the example of Facebook, as yet the most used social media platform, and examine its earnings. In 2020, it is estimated that 97.9% of Facebook’s revenue was generated from advertising, which amounted to around 86 billion US dollars2. To earn that amount of money, a full-time minimum-wage worker in the United States would have to work for over 5 million years. This type of profit is the reason that data is so valuable in our digital age and has required increased management and adjustments within law over the past decade. According to Ofcom’s research, 38% of internet users in the UK say they are “very confident” about managing access to their personal data online. However, the statistics also show that 44% of these people turned out to be unaware that information about them can be collected through their smartphone apps. Only 39% of total internet users are aware of all four ways in which online companies can collect their personal information. This form of data collection poses some important ethical and philosophical questions on privacy that add to the discussion brought to mainstream debate by Edward Snowden’s global surveillance disclosures in 2013.

You may ask what the problems are with social media being designed to become addictive. Indeed, the apps provide a chance to connect, create and form supportive communities. The internet is a platform that allows artists to share their work and gain visibility. Digital communication can break down the distance separating families and friends. A video call or old photo can provide relief for people suffering from loneliness, as has been shown throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. The internet is a valuable educational resource that means that anyone with access to it can learn about anything at any time. The issue lies in the fact that with addiction comes loss of control. When a service is powered by algorithms with which human intelligence cannot compete, those who are vulnerable to addiction or misinformation fall victim to the flip side of the coin.

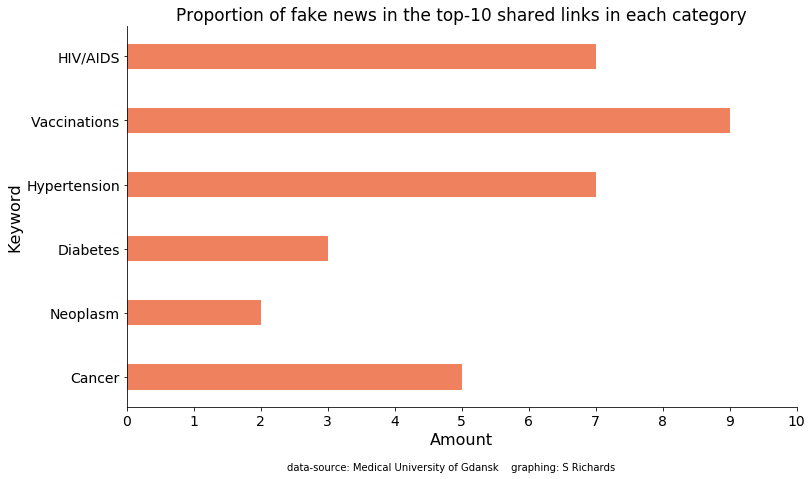

The Social Dilemma explores the effect that social media has had on the world’s political spectrum over the last decade. It demonstrates how political campaigns powered by social media may have led to an increase in affiliations to extremist parties and how they have become a threat to democracy as we know it. These persuasive technologies and the data we give them produce an undeniably effective way of grouping together people who think alike whilst feeding them information tailored to play on their emotions. Users are presented with the media they are most likely to watch and identify with based on their interests and internet habits. This leads to conspiracy theorists, from flat-earthers to the frankly more dangerous anti-vaxxers and climate change deniers, being consistently fed material that affirms their beliefs. This internet propaganda leads to the type of hysteria that was seen at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, as people ripped down 5G towers, believing them to be causing the spread of the virus3. A topic brought up in the documentary which I want to discuss further is the genuine threat that misinformation is causing to public health. A recent Polish study (2018)4 showed the extent to which online medical news contains incorrect or misleading facts. They divided the information found online in the most-shared medical articles into five categories:

- Fabricated news (information that was found to be completely fictitious);

- Manipulated news (basic and generally true information, but false conclusions or recommendations coming from the over-interpreted or overly extrapolated results);

- Advertisement news (stories often critical towards conventional therapies, designed to advertise ‘miracle’ products and ‘alternative’ treatments);

- Irrelevant news (not actually related to health at all);

- Sufficient news (generally true and evidence-based information about the disease in question).

For the purpose of the study, the categories of fabricated, manipulated and advertisement news were considered ‘fake news’. The researchers discovered some alarming results. Overall, Facebook activities accounted for the majority of total shares and engagements. Different topics attracted public attention with an unequal distribution (mean total shares, in thousands): cancer (34), neoplasm (18), vaccinations (15), heart attack (7), AIDS/HIV (7), hypertension (5), stroke (5) and diabetes (2). The topic most contaminated with fake news was vaccinations (90%), followed by hypertension and HIV/AIDS. Sufficient news represented only 19% of the studied material (mostly concerning heart attacks and strokes). This type of mass misinformation leads to people rejecting scientifically proven treatments in favour of alternative methods. In recent years, the world has seen an increase in avoidable deaths due to diseases such as the measles and HPV. The question on how to control for this medical misinformation is a difficult one with the necessity of maintaining free speech in a democratic nation. However, it is a conversation that needs to be had, given the severity and dangerous nature of some of the pseudo-therapies presented to people through their feeds and search engines.

The other subject on which I would like to extend the discussion is the effect of social media and tech addiction on mental health. As the documentary notes, children born after 1996 have been the first to experience social media during secondary school. Nowadays, a large part of most children’s social development is online. This affects their understanding of social identity, status and validation. They have also been the first generations to grow up experiencing the short-term dopamine hits that come with these internet interactions. The documentary brings up some concerning figures on US rates of children suicide and self-harm. Since 2009, when social media first became available on mobile devices, the US has seen an increase of 62% in hospital admissions for self-harm in 15 to 19-year-old girls and a 70% increase in suicides. These same increases are of 189% and 151% for 10 to 14-year-olds5. It is not an American-only affair. A recent BBC investigation has shown that in the UK, hospital admissions of 9 to 12-year-olds because of self-injury are averaging 10 per week, a rate which has doubled in the last six years6. These figures are indeed disturbing and clearly need to be acknowledged. However, although they coincide with increased tech addiction and social media usage among children, I believe it is important to check whether we have a situation of correlation or causation. Blaming such a severe problem on the wrong cause could be detrimental to young people getting the help they need. For this reason, Brigham Young research university performed an eight-year longitudinal study on the impact of social media on children’s mental health (2020)7, one of the very few of its kind. The study acknowledges the fact that rates of depression, anxiety and loneliness have sky-rocketed alongside the popularisation of smartphones. However, through the annual study of adolescents between the ages of 13 and 20 over a period of eight years, the research shows that there was no evidence that time spent using social media influenced the individuals’ mental health. This suggests that rising issues within adolescent mental health are more complex and not directly caused by social media exposure. Unfortunately, previous research shows that social media use is definitely at least associated with higher levels of anxiety, depression and overall psychological distress. This indicates that social media usage still needs to be taken into consideration in this discussion on mental health. A previous study by the University of Illinois (2015)8 demonstrates that negative mental health outcomes associated with use of social media, here referred to as Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), depend on users’ motivations. It proposes the security blanket hypothesis, a metaphor used to explain the fact that ICTs provided adults in the study with a coping strategy (specifically avoidance coping) when faced with emotionally charged events. When presented with a stressor, the participants who were allowed access to their mobile phones for distraction showed a decrease in anxiety, demonstrating that the usage of their devices was a coping mechanism. The research paper then discusses how this escapism provides short-term relief and negatively influences their psychological state in the long-term, especially within depression or anxiety predisposed individuals.

“Becoming reliant on an external device for comfort can be maladaptive because healthier coping mechanisms do not have a chance to be properly developed, implemented, and practiced. Indeed, other coping strategies such as task-oriented coping, which involves analyzing the stressful situation and processing how to deal with it, has been shown to be correlated with lower anxiety and depression than avoidance - and emotion-oriented coping.”

“Computers in Human Behaviour - avoidance or boredom: negative mental health outcomes associated with use of Information and Communication Technologies depend on users’ motivations”, University of Illinois

In summary, although research suggests that smartphone usage is not the cause of the rise of mental health problems in young adults, it does indicate that it is often a maladaptive and unhealthy coping strategy that can aggravate symptoms in the long run. Whatever you want to call this habit - emotional buffering, digital pacifiers, escapism, avoidance - it is a form of repression. Instead of feeling and processing the emotion as it is experienced, it is numbed through consuming a feed of information that ‘resets’ the brain with a short-term dopamine hit. Reliance on this unhealthy coping strategy stops users attending their emotions in a mindful way. Therefore, while excessive social media usage cannot be directly attributed to the rise of mental health issues in young adults, it can be linked to the severity of them. The same can be said for political disparity; it is a phenomenon as old as politics itself, but social media has arguably deepened these divides, connected extremists and decreased tolerance of alternative opinions. These issues are all the more unsettling considering that free app-store content is specifically designed to fuel addiction through habit-forming algorithms. All of this, along with the fact that exposure to fake news is unavoidable for many, poses some ethical questions on how such a force should be managed. By having these conversations and opening up these dialogues, society can re-learn how to navigate the internet as a tool rather than a detriment that steers us away from our goals, values and fulfilment.

1 “Adults’ Media Use & Attitudes report”, 2020, Ofcom https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0031/196375/adults-media-use-and-attitudes-2020-report.pdf

2 “Facebook’s advertising revenue worldwide from 2009 to 2020”, 2021, Statista https://www.statista.com/statistics/271258/facebooks-advertising-revenue-worldwide/

3 “Mast fire probe amid 5G coronavirus claims”, 2020, BBC news https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-52164358

4 “The spread of medical fake news in social media –The pilot quantitative study”, 2018, Medical University of Gdansk https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211883718300881

5 Figures sourced from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. CDC

6 “Concerning rise in pre-teens self-injuring”, 2021, BBC news https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-55730999

7 “Computers in Human Behaviour - does time spent using social media impact mental health? An eight-year longitudinal study”, 2020, Brigham Young University https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563219303723

8 “Computers in Human Behaviour - avoidance or boredom: negative mental health outcomes associated with use of Information and Communication Technologies depend on users’ motivations”, 2015, University of Illinois https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563215303332